When you think of a precision airstrike, what normally comes to mind?

Better yet allow me to ask a series of other questions…

Who do you think makes the decisions? How many people and processes do you think are involved in conducting these strikes? Who is ultimately responsible for the end result? What is a weapons system?

Once you begin asking yourself some of these questions, you’ll be on the right track. But if you are at this time under the impression that pilots, planes, and bombs are the answer to all of these questions, then prepare to be enlightened.

This working paper will attempt to provide you with some understanding to answer some of these questions, and will hopefully give you an insight into some potential ethical problems with the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and perhaps even an insight into how atrocities such as the bombing of civilians without soldiers and airmen challenging the system can happen. In doing so, this paper also seeks to help further a more comprehensive dialogue toward the understanding of warfare and societies at a human level. These are my reflections as I go, and I hope that people will feel compelled to participate in the development of this project in a critical way, whether that be of my writings or in order to add to them.

Words on the diffusion of responsibility and desensitization to conflict

When I was opening up to a good friend to explain why I felt a personal responsibility for my work in Afghanistan and how it still affects me, she told me another much more relatable example of a problem that plagues our society today. H&M, a store we’ve all shopped at some point is a store that actively uses sweatshop labor for the production of its goods. She said that if she shopped there, she’d be guilty of perpetuating that system of labor. But if she didn’t and ran a campaign that stopped people from shopping there, then perhaps one of these sweatshops will close, but leave many people on the streets, or worse, it may burn down with everyone trapped inside. This she said was one of her reasons to pursue politics. We currently live in a system that is blind and desensitized to the ingredients that facilitate our way of life. Knowingly and unknowingly, we support systems of cruelty around the world with our every purchasing decision. If you ever bought a cellphone, quite likely you indirectly paid a person who actively uses slave labor. If you eat meat, you more than certainly contribute to millions of pigs, chickens, and cows living in factory-like conditions that are subject to unimaginable cruelty every year. Perhaps a person against their own interests exposed a corrupt and anti-constitutional system of spying on their own citizens. In our society, there seems to be five approaches to this.

- Willful ignorance and/ or apathy.

- Abolition of self responsibility by rationalizing oneself out of the decision-making process.

- Mistrust of negative information, while blindly supporting the views of the authority figures.

- Vocal outrage while still persisting their purchase of said product, albeit guiltily so.

- Absolute rejection of the system, while actively looking to change it.

Guess which four pathways most people choose? What do you do when confronted with issues such as these? Well, you might ask what one person changing their habits could do to change an entire system? Maybe you try to rationalize it into a general acceptance of cruelty as a fact of life. Maybe you just ignore it. We are surrounded by interconnecting systems of injustice just asking to to be revealed, but as a civilization we are perpetually concerned with our own self comfort, and are hard pressed to look outside ourselves and relate to the cycles of suffering we help to exist globally. Our brains are wired to interact with communities of no more than 300 people. Within that group of 300, altruism is often quite prevalent. We will spend great sums of time and money to save a puppy from being euthanized for instance, while at the same time pass a homeless woman with her children on the street without batting an eye. Maybe we’ll say to ourselves, “she’s probably a scam artist”, or “someone else is supposed to help her, where is the state?”, it’s “Somebody Else’s Problem”. If enough people stand idly by, we are anti-conformist if we act. This is called the “bystander effect.” It is therefore no stretch to say that this problem persists in the military and politics as well.

In 1961, the Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram devised an experiment three months after the start of the trial of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. It sought to answer the questions “ Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” The results of these experiments were quite stunning. Milgram summarized the experiment in his 1974 article, “The Perils of Obedience”, writing:

“The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous importance, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects’ [participants’] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects’ [participants’] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.”

Six years later – at the height of the Vietnam War – one of the participants in the experiment sent correspondence to Milgram, explaining why he was glad to have participated despite the stress:

While I was a subject in 1964, though I believed that I was hurting someone, I was totally unaware of why I was doing so. Few people ever realize when they are acting according to their own beliefs and when they are meekly submitting to authority… To permit myself to be drafted with the understanding that I am submitting to authority’s demand to do something very wrong would make me frightened of myself… I am fully prepared to go to jail if I am not granted Conscientious Objector status. Indeed, it is the only course I could take to be faithful to what I believe. My only hope is that members of my board act equally according to their conscience…

Milgram’s experiment revealed something unwelcoming about human nature, something most people would emphatically deny. We humans are pragmatic creatures who believe themselves to be principled in times of calm, but are more often than not weak in the face of gross injustice when in the presence of authority; whether it be institutionalized or of a majority of peers.

A separate but equally important experiment was conducted by the Stanford Psychology professor Philip Zimbardo. This experiment would come to be known as the Stanford Prison Experiment. It was funded by the US Office of Naval Research and was of interest to both the US Navy and Marine Corps as an investigation into the causes of conflict between military guards and prisoners. In the experiment, twenty four students were selected to take on randomly assigned roles as prisoner and guards in a mock prison. Well beyond the expectations of Zimbardo, the guards actually became authoritarian in nature and began subjecting prisoners to psychological torture. Several prisoners passively accepted psychological abuse, and consented to the requests of guards by harassing prisoners who attempted to prevent it. Zimbardo himself, acting as the superintendent found himself conforming to his role, exhibiting sadistic tendencies as well. This ultimately cause him to terminate the experiment, as it began to spiral out of control. The conclusion to this experiment favored situational attribution to behavior. Zimbardo argued that the results of the experiment demonstrated the impressionability and obedience of people when provided with a legitimizing ideology and social and institutional support. The experiment has also been used to illustrate cognitive dissonance theory and the power of authority.

The results of both experiments are both mutually reinforcing, it shows that people conform to roles in the best way they know how, and are by and large eager to do so. What does this say about human nature and the structures which persist in our society, and how does this relate to the diffusion of responsibility

No one person in the Nazi party claimed responsibility for the millions of people killed in concentration camps. The hierarchical nature of the party allowed minor bureaucrats to say that they were just following orders, and minor supervisors to say that they only issued commands but did not actually commit the deeds. When one pilfers through archives of confessions, this might be the common arguments one would expect to find. Concentration camps and their transportation networks were designed in manner which created separation between the operators and the prisoners themselves. From cultural indoctrination, they were taught to hate the Jews and see them as lesser beings. Linguistically, Nazis developed official words that were used in common language to make genocide more palatable. A concentration camp official might write home bragging about the “units” he processed that day to his wife, while in the same paragraph telling her how proud he is of his daughter’s grades. Language being our principal means for constructing our reality, is, and has always been used to manipulate perceptions. With each label and each choice of verbiage, it will determine whether we view an action as justifiable or unacceptable, authoritative or subversive. In today’s society, politically loaded words are thrown around constantly, and people are often left unaware of their own emotional manipulation. The military institutionalized this into their vocabulary with the use of emotionally neutral words to describe often controversial topics, and acronyms to describe complex interactions in order to speed up communication and obscure information to non- military ears. It also unofficially uses slang to refer to “others” in a derogatory manner. The culture of the military is often seen from the outside and internally as an exclusive group. Below are a list of terms used, that could be said to have a hold on the US military/ public image of military’s mindset:

- Shake and Bake : a combination barrage of White Phosphorus and explosive artillery shells. Also an American side dish of potatoes.

- Haji: used to describe any person with a brownish skin-tone. Often it is use derogatorily. Actual meaning is someone who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca. In practice, it conflates race with the Muslim faith, and is a label used to identify and “other”. It could also conflate religion with belligerent actors.

- Target: used to describe anything of potential military threat.

- Potential Enemy Combatant: used most in reports or official documents to describe people who were killed who they suspect of being a combatant, but lack adequate evidence

- Suspected Insurgent: Man of military age brought in or killed nearby, or suspected to be linked to insurgent activities.

- KIA: Killed in action. Typically used in referring to friendly forces who are killed in combat. Acronym obscures the emotional response one would have to the word “kill”

- Optics: The public eye (opinion)/ the perception of the man in the street. It is used to obscure text which refers to public opinion

- Collateral Damage: Destruction of unintended infrastructure or the killing of non-combatants (ie. women and children)

- Enemy assets: Roads, bridges, weapons, communication networks, guarded information, and soldiers/ suspected insurgents

- Deconflicted/ Attrited/ Degraded: words that are used in place of “killed”, typically for the purpose of awards packages, EPRs, or other official military documents.

- To Attrit: Means to blow into smithereens; sanitization of destruction

- Fog of War: A term used to justify mistakes or atrocities committed during combat

- Embedded Journalists: Journalists who travel with soldiers and report favorably on the US war effort

- PBIED: Person Borne Improvised Explosive Device; meaning suicide bomber; used in order to not provoke offense

- GWOT: Global War on Terror; refers to all operations, including clandestine operations conducted in the effort to stop terrorism

- EIT: Enhanced Interrogation Techniques; this refers to coercive interrogation tactics such as but not limited to waterboarding and sleep deprivation

- Black Site: locations where they are neutral non-signatory to any torture prohibition treaties. Metaphor used to make it sound more acceptable.

- HVT: High valued target; used for people on terrorist watch lists or those who are valued for their information

- EPW: Enemy Prisoner of War

- Illegal Combatants: Term that replaced EPW to avoid conditions protocols in the Geneva Convention

- Renditions: Removal of EPWs to countries where use of torture in interrogation is condoned. Used to make it sound more acceptable

- Surge: Refers to the deployment of troops; originally called an “escalation” then changed to “augmentation”.

- WMD: Weapons of Mass Destruction; reduced to an acronym to demote after claims of Nuclear Weapons

- Friendly Fire: Used to describe shootings of soldiers belonging to the same side; the purpose is to avoid reality and neutralize emotions on killing people

- CW: Chemical Weapons; acronym that sanitizes death

- Smart Bomb: Refers to precision guided munitions (missiles); this is used to connote to the public that they are extremely accurate and are a good military option; sanitizes death

- Cluster Bomb: these are “dumb” bombs which are released indiscriminately over a targeted area, that often don’t explode and litter populated areas; it does not represent reality

- Daisy Cutter: a bomb called a Blu-82 which is used to flatten areas for helicopter landing and as anti-personnel/ intimidation weapon due to its large lethal radius; name used to sanitize death.

As one can see, there are clearly many ways that are used on the military and the public to suppress or drum up certain emotions. Words and phrases such as these work to create a certain lexicon of speech peculiar to the military.

Once one is put through the process of basic military training which entails the breaking down of an individual and the building up through the image of the military, s/he is taught to follow orders with extreme attention to detail, s/he is bound and made accountable to their fellow servicemen, and are thus effectively made able to perform as an individual whose actions and inactions have consequences for an entire system in a very short amount of time.

Words such as those listed above, as well as acronyms become a peculiar part of his or her vocabulary and mode of thought. The military therefore has multiple ways it can make the action of killing human beings easier and more effective.

A system of hierarchy is etched into the minds of every recruit, one that requires a soldier to answer to his officers so that they do not answer for him. It makes Non Commissioned Officers and Commissioned Officers alike responsible for the welfare and the good conduct of their troops.

Once a civilian signs his contract and swears his oath, he is no longer his own property, but that of the government of the United States of America. From then on, they have the authorization to send you where they wish, and make you do what they wish. Applying for Conscientious Objector status at this point becomes less credible, and requires one to go through a great deal of humiliation and legal work. For disobeying orders on the basis of negligence or disagreement, one is potentially subject to career ending punitive paperwork that could ruin ones chances at promotion or worse, their chances of employment as a civilian.

Concerning the diffusion of responsibility, I have outlined several contributing factors one must take into consideration as I explain how a modern air strike may be conducted. It is important to consider the human psychological elements of submission to authority, conformity to roles within different social contexts, the use of language as a program for thought in the US military, hierarchical command structures, and the repercussions for disobedience when explaining the environment this diffusion of responsibility takes place. The last linkage to make of course is how modern technology itself, as well as the specialization of roles contribute to this diffusion. To do this, I will offer my brief interpretation on the historical progression of technological causes, as well as structural causes for the diffusion of responsibility over time, in which I will eventually come to describe modern conflict.

Progression of the diffusion of responsibility

Up until the invention of gunpowder, there was primarily only one way for soldiers to kill people, and that was to do so directly with whatever weapon they had at their disposal. Be it a sword, a mace, a bow and arrow, or a trebuchet; the kill decision was in the hands of the soldiers. The soldier and his weapon was effectively a weapons system. But even then, he was trained for combat by his superiors, he had a commander to take orders from lest he risk severe punishment or death, and he had very little say over what battles he’d fight. Moreover, without people making his weapons he was ineffective, and without armor he was vulnerable. Arguably, the first example of the technical diffusion of responsibility was through weapons like the trebuchet, as it often required a team to operate. No single man was responsible, but all men were needed to ratchet the pulley back, load it, point the machine, and then release the triggering mechanism. These machines were mostly used as siege weapons and the soldiers operating them were often dual use (as in they also served as infantry), but from this point warfare evolved.

Warfare in those days was brutal, just imagine marching onto a field knowing good and well that you would most likely be killed, watching the men beside you being filled with arrows while you continue toward a storm of blood, flesh, and metal. History depicts these battles as glorious meta-events, but it rarely focused on the effects it had on the soldiers themselves. It’s true that these men must have been more hardened and/or desensitized to this kind of violence as a result of their training and societal upbringing, but these events were moments of absolute trauma, adrenaline, and fear. In such instances, desensitization to this level of violence was crucial to an army’s success, as those who were not, most likely perished.

Physical distance is also emotional distance. The advent of gunpowder made it so that human beings could kill each other more easily, without the years of training it took to create professional soldiers. Numbers rather than skill became the most effective measure for an army’s success or failure. One only needed to instill the discipline to stand there and be fired upon while having the ability to reload, fire and point his rifle. During this time, these men were constantly aware of the fact that if they did not fight, they would be lanced in the back by their officer in charge. It was therefore hopeless either way, and one was just lucky to make it out alive. Morally, the choice to kill was merely an option of choosing to live or die. But even so, PTSD existed during such times. In the American Civil War, it was called Soldier’s Heart and was treated as the name implies, as a heart condition. War was still extremely brutal at this point too, once armies exhausted their ammunition, they were expected to charge with bayonets. Nevertheless, there was never a question of who was responsible, it was clearly officers, soldiers were just helpless pawns.

World War I saw countless new advances in diffusionary weapons systems. Tanks, landmines artillery, airplanes, and chemical weapons all made killing more simple and required less personal accountability. They were also vastly inaccurate, but absolute destruction was the objective. Rather than counting deaths in the hundreds or thousands, this war was counted by millions. Shell shock became a new term to describe those who were traumatized by the violence. Rather than standing in rows, individual soldiers regained their individual importance on the battlefield to an extent. Trench warfare introduced prolonged engagements and a new level of uncertainty, it caused men to endure siege conditions on either side on a daily basis who were not trained to do so in the least. Under these conditions, morale was difficult to enforce, and thus men were left fighting their own battles to survive. It was unclear for them why they fought, and time spent in those trenches gave way to thought, which ultimately contributed to a humanization of the individual soldier in literature and in popular culture. Conversely, while brutality was broadly existent on the receiving end, the artillerymen, the tanks, and the bombers in the aircraft normally attacked from a great distance, and were not exposed to the destruction they were inflicting.

World War II was as much a war of propaganda as it was one of new advances in weaponry. Soldiers became more valued as individuals, and the painting of the “other” was as much for soldiers as it was for entire populations. Commanders and officers could distance themselves from the battlefield with radio technology, and logistics became more structured and consistent with the advances in transportation and communications. Warfare began to take on a more systematic quality and specialization became a means of making battlefield operations more efficient. Air warfare was itself able to begin diffusing its responsibilities with the introduction of several new technologies, particularly the radio and the radar. As in all standard aircraft, bombers had a pilot and a flight engineer who acted as the copilot. There was a navigator, who navigated. But then there were radar operators who scanned the ground for targets, bombardiers that calculated trajectories and released bombs on the targets that were selected by the radar operators, wireless operators that communicated with the ground/ scanned for enemy aircraft/ jammed enemy aircraft signals, and gunners were responsible for protecting the plane while in flight. Together they were all essential for the mission to succeed, but ultimately the flightpath, the target selection, and the kill decision was restricted to those on board the aircraft. General orders were given to the crew by a commanding officer, and those on board acted under radio silence autonomously, a measure used because of poor cryptography. This weapons system was less concerned with collateral damage as it was out of the hands of control of the operators. Technology simply did not exist at the time to effectively avoid it. It was responsible for the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nevertheless, in that time, questions of responsibility weighed on the shoulders of the crew of the Enola Gay and the Bockscar, regardless of the absence of regret for doing so as they viewed it as necessary, but were still confounded. Being a bomber at that time was one of the most dangerous jobs in aviation. Additionally, they had their country behind them. The media influence sufficiently dehumanized the enemy to the point where such measures were seen as an acceptable outcome. This isn’t to say that the enemy did not demonize themselves on their own, but it certainly acted as a powerful force in extinguishing the ethical question over such uses of force.

The American war in Vietnam was a turning point in the public eye, from being a liberator to being a policing force. Unlike the Korean war and those before it, it was viewed as entirely unnecessary and asymmetrical. The free media in the absence of a looming direct threat; once employed to inform and rally its citizens around the use of force for its own good, became a liability to the powers at be. War reporting revealed the massive abuses of American power, the same vacuums in morale as the Great War were created and exaggerated, and people were cynically killing others out of fatigue and angst. Search and Destroy missions was code for slash, kill and burn everything that stands. The dense jungles, the absence of clear military and/ or political objectives, and use of guerrilla warfare by the enemy wore down the Americans as much as the trench warfare did almost half a century prior. The jungles hid an invisible enemy, much like the inaccurate bombardment and gassing it presented a deadly force impossible to defend against. It brought back close quarters combat, the kind in which soldiers half a millennia prior where trained years for to withstand. With sheer brute force and hatred, the American military used its advanced weapons of war to annihilate and demoralize the enemy into surrender, but it didn’t work. Moral superiority was not on the American side. As in the previous wars, the revered and respected American soldiers on the ground were conscripts, they were not volunteers. They were less disciplined than today’s soldiers, and they were unsupported by their own population. They fought their fear with violence, and came home bastardized, bitter, guilt ridden and traumatized. On a similar but different token, pilots and aerial gunners on average were responsible for the greatest atrocities: dropping cluster munitions of which still remains today, agent orange which burned entire forests, and gunning down entire villages of civilians. Yet in the midst of all this, they felt the least amount of connection to their actions. One reason for this was their command structure. Rather than all airstrikes being ordered by a single commander, requests for airstrikes originated with the 2nd Air Division and Task Force 77 in Vietnam and then proceeded to CINCPAC, who in turn reported to his superiors, the Joint Chiefs, at the Pentagon. After input from the State Department and the CIA, the requests then proceeded to the White House, where the President and his “Tuesday Cabinet” made decisions on the strike requests on a weekly basis. In addition to this complex command structure which diffused the decision-making process, precision guided munitions were newly introduced into common use, and required it’s own technical crew behind it. Targets were painted with white phosphorous smoke by Forward Air Controllers in small prop driven planes. Then bombers were radioed over to the general coordinates and they dropped their payload of whatever bomb was available.

When I went to Afghanistan in 2009, in simple words, my squadron set up the system which offered Battlefield Command and Control. We connected the soldiers on the ground to the battlefield commander, and the planes which were to deliver their payloads.

In less simple words, that I am aware of, our system maintained 250 +/- nautical miles of persistent data, radar, and radio transmissions between radar operators, battlespace managers, Tactical Air Control Parties, Joint Tactical Air Controllers, UAVs, satellites, imagery analysts, pilots (both UAV and manned), sensor operators, troops in contact, the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node, the Air Support Operations Center, and various individuals located at the Combined Air Operations Center in Al Udeid.

As this was happening, I would often sit inside the Radio Control Unit and imagine the airstrikes as they were being conducted while I’d perform diagnostics on all of the equipment. It was difficult for me to fathom how instrumental the radios I put there and programmed were to the entire war effort in Afghanistan. With addition to airstrikes, they enable reconnaissance, airlifting cargo and supplies, and medical emergency transport. On the one hand, I knew that this mission enabled new capabilities which morphed the way warfare would be conducted in the future, hopefully improving the safety of troops. It was a movement into the realms of Network Centric Warfare. But within this realization, I also realized that we offered a key instrument for UAVs to conduct their missions. I questioned where responsibility lay in such a new form of warfare. Was it with the battlespace commander? Was it the pilot? Was it the intelligence analyst choosing targets based on reconnaissance imagery? Was it the JTAC talking to the plane, or the TACP coordinating with the ASOC? Am I responsible for building the network to facilitate all of this as was Oppenheimer for building his H-bomb?

Here I stood, only 21 years of age after my NCOIC called us over to our equipment to congratulate us on a job well done and to tell us we were killing bad guys now. Trying to maintain my composure in front of everyone else, it dawned on me what my place was in this war. War being something I never truly felt an affinity for, I always believed that we are what we are, based on what we do. Something within me rose, and I experienced a moment terror for what I had just participated in. If we are what we do, then what did that make me? My ambition to leave the military without harming anyone left out the window with my innocence. I sat in that RCU often, torturing myself with my own imagination as I pictured strike after strike. I wondered who it was at the receiving end. Was it Taliban, an angry father whose home was bombed killing his whole family, or was there a child there?

For a month until I left, a sense of dread lay for what my Enlisted Performance Report would say. Ultimately the day arrived after a month or so of being home, the work this system my unit built supported 2,400 Close Air Support Missions and 200+ enemy kills. That night, by way of the internet I cross referenced this report with the report by the UN’s Annual Report on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. I waited until early 2010 to see what it said:

“UNAMA HR recorded 359 civilians killed due to aerial attacks, which constitutes 61% of the number of civilian deaths attributed to pro-Government forces. This is 15% of the total number of civilians killed in the armed conflict during 2009.” page 17.

It was all that mattered for me… My nightmares began in Afghanistan, where we had experienced rocket attacks almost nightly, with the threat of a ground attack which ultimately resulted in a suicide bombing weeks later, and with knowledge of a mortar landing close to me. I’d wake up throughout the night, sometimes rolling onto the floor with the assumption that we were under attack. But after this system went online, these nightmares morphed into ones where I was standing in a village being bombed with full knowledge of my role in it, while I’d desperately try to help save people. Upon returning home I’d wake up with nightmares of a child standing next to an ash covered body looking at me as if I had done it. I’d reach down and frantically try to revive the corpse to no avail, and the child would just continue to stare at me as if all hope had left her body. Sometimes I would dream of the reverse happening, a mother and father with a dead baby in the mother’s arms, screaming in grief.

I never needed to see the horrors of war, my imagination already haunts me. I feel the weight of my responsibility for my actions there, even if the majority of my peers don’t seem to. This weight continues to grow with each passing day, as the death toll rises. I can’t help that. Knowing what I know, I can’t in good conscience keep pretending everything is ok.

At my going away party, a joke about burning my uniform turned into an action which left a few former colleagues feeling uneasy. Ruining my boss’s grill was a regrettable way to try to separate myself from my experience, but it didn’t seem to work. Temporarily it did, on my post Air Force travels, until my trip lead me to the Republic of Georgia to a town called Gori, a place I visited as a tween while my father worked in Armenia as a US Defense Attache. Two years prior to my revisiting in 2010, the Russians bombed the town killing over 60 people. I suffered a near nervous breakdown in front of a bombed out apartment building and bawled my eyes out in the square next to the Stalin museum. From that moment, I’d say I was lost, trying to find my way toward redemption. I needed to connect with something that would give me back a purpose, so for a time I was determined to return to Afghanistan and apologize to anyone that would hear me. But I was stopped by a Russian Afghan war vet I met in Kazakhstan who assured me that my answer was not there. He himself tried to go back to reconcile with his actions, and he showed me his gunshot scar to prove it. So I decided to heed his advice and go to school, studying International Relations instead. Of course, when you feel like you have blood on your hands and bare a tremendous sense of guilt for that blood, the subject matter of international relations has an easy way of whittling you away. Till last summer, I didn’t know how to deal with my past. I broke down as my life seemed to be falling apart, but as a result I have managed to regain composure and come out of it. Hopefully, in a more useful capacity.

Being the person I am, I was never afforded the luxury of being content with causing pain to others. I yearned for a way to channel my experience into something beneficial for humanity. It’s incredibly difficult not to dwell on it now, as I view my own life in the context of a deficit I owe to those people who’s lives I helped ruin. As this deficit builds, so too does my motivation to do something positive. Honestly, so does my guilt sometimes, but I’m working on that. Terminating myself isn’t the answer, and I’m not supporting that mindset. I’m simply calling for awareness, dialogue and a new way of thinking.

Network Centric Warfare and Full Spectrum Dominance

Network Centric Warfare (NCW) is a military doctrine and a theory of war that was conceived in the 1990’s. It was first mentioned in a paper called “Copernicus: C4ISR for the 21st Century” in describing the US Navy’s approach to the information age.

A commander’s greatest challenge is to maintain situational awareness on the ground on the location of his own forces. There are various systems that were developed to support this technologically, among them being the Global Positioning System (GPS). GPS effectively allows combat troops on the ground to locate themselves on the battlefield, but does not create an automated/ integrated system for reporting that information.

To build a theoretical model for how this works in practice, I will use the example of a Marine Air to Ground Task Force (MAGTF). In order to progress, there are two assumptions one must make. First, the Marines on the ground as well as the attack aircraft know their own location with GPS. Second, they possess communications platforms to transmit this data. By automating this process, the MAGTF now has the ability to know the location of every Marine, as it is provided a database that can be manipulated and analyzed either locally or remotely.

The next stage is to provide this data to every weapons system that provides automated firing solutions ie. artillery, naval gunfire, aircraft. These weapons system can now avoid “friendly fire” by using the positional information made available to them across this network platform. Going one step further, it will provide all units with target identification and designation by automatically feeding this information into this network. By doing this, it provides both air and ground based automated weapons systems the ability to conduct a battle in real time, while avoiding friendlies on the ground and to hit their designated targets with near-pinpoint accuracy. With the information provided in this network, the Direct Air Support Center (DACS) can assist in coordinating Close Air Support (CAS) by making the network aware of all available aircraft and armament in the area. By connecting other systems, this network can be provided with an infinite platform for information.

Once the ground, air and naval fire support elements, the ground units, and the coordination agencies have been integrated into the network, this system is now able to coordinate and provide fire support at the speed of a radio signal. By giving all of this information to every weapons platform, the network, with sufficient computing power can identify every element. The network can therefore compute the most effective firing solution, and either a human or the network itself will be able to select the appropriate system.

Future, if not already existent uses of this network centric approach are exponentially numerous if applied to every sector of the Department of Defense. Planners envisage real time coordination with medical systems, medical diagnostic feedback with individual soldiers, and real time status updates on ammo usage, thus allowing for the network to provide instantaneous resupply of ammo or arrangement of medical evacuation (MEDVAC).

NCW is the coming together of three elements: the sensor plane, the shooter grid, and the information grid. It is our current state, and it is the future of warfare. This system is integral to the US military’s other objective of Full Spectrum Dominance (FSD). FSD is a doctrine which one might consider, the practical implementation of George Bush’s declaration of global American hegemony in the lead up to the Iraq War in 2003. FSD is essentially the vision of total dominance in naval (surface and submarine), air, space, ground, electronic, and informational warfare. Whether or not this can be achieved is a valuable question to ask. With ubiquitous collection of information across every platform interconnected by a thinking network, it’s clear that the United States has the distinct advantage. But the United States is not the only power with the ability to create such a system. It also does not consider the asymmetrical tactics which will be developed and employed to combat it. Nevertheless, this network is instrumental in the further employment of UAVs and other automated weapons platforms and encourages further diffusion of individual responsibility for killing. At this point I find my greatest disconnect with how modern warfare is conducted.

The foretold advantages of NCW is that it will ultimately help prevent friendly fire and will improve battlefield logistics. But the potential repercussions of this system is that decisionmaking is taken up and diffused by the network itself, thus eliminating what should be the difficult decision to use deadly force. Already within the US military, soldiers are psychologically pre-conditioned by traditional hierarchy, social roles, specialization, fear of disobeying or lack thereof for exceeding expectation, social acceptance, and linguistic manipulation to be less sympathetic toward the use of structured violence. Through the use of UAV technology, pilots are no longer even put into harm’s way. With the prevalence of military video games utilizing methods of killing such as Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 that are identical to images one would see in their combat missions, it is easy to understand where several disconnects with reality might lie. By diffusing the process further, and/or pushing toward further autonomy with weapons system as seen with the US Navy’s newest addition the X-47B, how can ethics or the Geneva Convention for that matter be upheld? Assuming there ever is a day when culturally acceptable, who will be held responsible for war crimes committed?

A modern air strike works as follows, although these scenarios are fictional and may include some inaccuracies. This is more to illustrate the complexity of aerial operations than to provide operational details.

Location: 40 km north-west outside Gereshk, Helmand Province, Afghanistan

Situation: 12 man Army reconnaissance team are ambushed by what appears to be at least 30 anti-coalition militants from the side of a mountain sitting directly at their 2 o’clock position. They are sustaining heavy gunfire and artillery bombardment.

Airstrike type: Dynamic Targeting ( Time sensitive), friendlies in the area

Scenario 1:

Team Without Forward Air Controller:

- Soldier switches his Land Mobile Radio to a special frequency, calling for artillery bombardment and air support.

- Signal is intercepted by Battlefield Airborne Communications Node, it is transmitted to the 73 EACS where it is interlinked with radar and data and sent to the Battlefield Command and Control Center Al Udeid, it is also relayed to the Air Support Operations Center (ASOC) for authorization.

- The signal is also intercepted by a nearby Fire Support Officer who controls artillery stands by for coordinates and authorization

- GPS coordinates are instantly made available to the network, and the soldier approximates the distance and direction of where the fire is coming from in relation to his location.

- Through BACN and the 73 EACS platform, the operators in Al Udeid and Kandahar coordinate to send the closest available attack aircraft in the area.

- The selected aircraft diverts its flight path and goes enroute to the location, then first does a flyover.

- Sensors and video footage are fed into the network and targets are selected by operators

- Coordinates are shared with the Fire Support Coordinator (FSCOORD) who coordinates with the Corps Artillery (Corps ARTY), Division Artillery (DIV ARTY), and the Field Artillery (FA BN) units to

- This data is at the same time sent from the Air Support Operations Center ( ASOC ) to the Combined Air and Space Operations Center (CAOC in Al Udeid) for approval by the JFACC

- Approval is granted.

- The pilot loops around and does a second flyover, this time he presses the button releasing the munitions.

- The FSCOORD then provides authorization to commence with artillery bombardment of the area

- Another flyby is done to assessing the damage, and to ensure that all militants have been killed.

Scenario 2:

Team with Forward Air Controller:

- Forward Air Controller (JTAC) or TACP gets on PRC-117 ( a combat net radio enabled for satellite communication and dual command and control) and sends a request for Close Air Support (CAS) to the Air Support Operations Center.

- The radio itself is interoperable with all flight radios, thus all pilots in the area are alerted to this.

- BACN also intercepts this signal, then relays it to all ground commanding officers in the area

- The TACP in the meantime sets up a data link with the satellite and prepares the sensors for operation.

- The network already picks up their GPS coordinates, so all weapons systems are instantly alerted to this.

- The TACP then directed the sensor at the intended targets, and this data is uploaded onto the network.

- This information is analyzed by intelligence officers, and targets are selected.

- In the meantime, the TACP keeps the sensor on the targets and updates the network to their movements.

- The ASOC reports the situation directly to the CAOC, then it is approved by the JFACC, if s/he is not present it goes to next in charge.

- An aircraft is designated by the air control operators in the CAOC, then it is diverted to the location.

- The TACP or JTAC is linked to the pilot and to the ASOC, and the TACP guides the pilot on the best method of approach.

- The missiles are already pre-programmed on the targets to attack, intelligence officers watch the live video feed coming from aircraft, listen to the TACP, and match that information with his sensor data.

- As the pilot makes his approach, he deploys the guided missiles and they hit the preselected targets

- The TACP reports on the damage, then the pilot makes another pass to provide an overview for assessment of the intelligence officers, and to scan for further threats

- If successful and all human targets are killed, the team of soldiers will then visit the site of the air strike and visually inspect the casualties.

Location: 70 km north-west of Wana, Pakistan, 20 km before the Afghan-Pakistani border

Situation: MQ-1B Predator armed reconnaissance drone spots 120 heavily armed men moving southeast on foot heading toward the border of Pakistan presumably to Wana. Based on recent intelligence in the area, these men are suspected to have been responsible for recent attacks on coalition troops.

Airstrike type: Unmanned Air Interdiction Mission, Dynamic Targeting ( Time sensitive)

- Drone spots a cluster of moving targets travelling in a single direction toward Pakistani border.

- Drone pilot begins to circle overhead fixing its sensors on the suspected militants

- The sensor identifies 120 men armed with AK-47s, 20 of which also carry RPG-7 Rocket Launchers.

- This information is sent directly in real-time to the satellite which is being used for flight and redirected down to the satellite receiver-transmitter at the 73rd EACS in Kandahar Air Field and Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

- The signal is diverted in real time to the CAOC and the Intelligence Officer/ Imagery Analyst who identifies and confirms that the selected targets are in fact anti-coalition forces by zooming in and visually inspecting them.

- Across the network, he also verifies that these men are not friendly militias by requesting verification from ground commanders.

- Once this is confirmed, a request for an airstrike is given, then it is rapidly authorized by the commander due to the time sensitive nature of the event. ( If the militants are allowed to cross the border, then the military commander will technically have to request entry from the Pakistani Government, which by the time it goes through, it will be too late.)

- Due to the drone’s limited supply of firepower, an A-10 is also called in for backup support instead of the drone using its two Hellfire missiles, which would be too little firepower to kill every militant, and would risk some escaping.

- The Predator continues to circle maintaining visuals on the cluster of militants at all times.

- This information is shared with the ASOC, who then directs the A-10 pilot on his initial approach.

- On the first approach, the pilot releases 5 of its 10 Maverick Air to Surface missiles to pinpoint locations on the row of militants to cause maximum casualties.

- In the meantime the drone continues to circle in order to give Intelligence and the Commander a situational overview. Its heat and motion sensors detect that all but 10 of the men were killed.

- The A-10 is then directed to make a second approach in which it employs its 30mm cannon to kill the remaining men.

- Once complete, a ground based assessment team is called into the location to inspect the bodies.

Location: Sangin, Helmand Province, Afghanistan

Situation: Local intelligence sources state that a High Value Target (HVT) who is major drug trafficker working with the Taliban is currently held up in a large house near the outskirts of Sangin. He controls a violent local militia who are positioned within the house and the surrounding neighborhood, making it too hazardous to send in troops. In addition, the drug kingpin is expected to have an significant arms and ammo cache in his home, making the home itself strategically important to anti-coalition activity in the region.

Airstrike type: Manned Air Interdiction Mission, Preplanned

- A surveillance drone is sent to the area in order to provide a persistent situational overview for planners to assess their intended target.

- The planning team builds up a list of targets based on the local intelligence given and uses the imagery to assess the potential for collateral damage ie. infrastructure and civilians that might be harmed unintentionally.

- This information is then used to designate aim points for the aircraft.

- The risk for high levels of civilian casualties is low, but it is expected that there will be some. Therefore it must be pre-approved by a higher ranking commander.

- Another a weapons planning team reviews the targets, and determines the best weapons to be used and the amount. It also determines the amount of aircraft needed, as well as the number of sorties needed for the mission.

- Next, this goes to a team that develops a Master Attack Plan.

- This plan then goes for approval to the commander who then weighs the military necessity of destroying this compound against the potential for civilian casualties and a fallout with the local population. With a ground based attack of the compound being ruled out due to the potential for suffering heavy loss, the commander considers the large scale anti-coalition presence in the area and the coming opium harvest in May. He determines that out of strategic necessity, the compound had to be destroyed, and the kingpin had to be killed with it, for the impact it would have on Taliban/ anti-coalition operations.

- This operation is then scheduled to take place the following morning

- In this case, it was determined that only two bombs would be used and only one aircraft/ sortie would be needed to collapse the building.

- The weapons are loaded onto the aircraft, and it sets off toward its intended drop zone

- Communications between the aircraft and the CAOC is managed via the satellite link between Qatar and Afghanistan via the 73 EACS. Operators manage air traffic in the area directing and tracking the movement of the aircraft to the bombing target. Information is shared with the ASOC.

- As the plane flies over, the bombs are dropped on the target’s compound, which results in a much larger explosion than was originally anticipated. The resulting blast effectively flattens every home within a 150 meter radius.

- Radio chatter between the CAOC, the pilot, and ASOC increase significantly as they try to discover what happened.

- The surveillance drone flying overhead detects people on the ground frantically running around trying to save people who survived the blast.

- The pilot inquires whether or not another pass would be necessary, to which the commander replies that he should get back to base.

- The next day, the mayor of the town contacts the governor of the region claiming that the strike resulted in over 50 civilian casualties

- The commander of the operation is alerted to this, then apologizes to the mayor and the governor and arranges for reparations in the form of payment.

- The area is still considered too hostile to assess what happened, but the commander suspected that the home was a decoy filled with explosives.

- In the official report, due to the inability for the military to send in a damage assessment team to gain first-hand evidence, it is stated that 50 potential enemy combatants were attrited (killed)

Expeditionary Air Control Squadron (CRC/CRE): EACS

- Detection, identification, and classification of all aircraft and missiles within the area of responsibility.

- Track management of each aircraft, missile, and ship.

- Data transmission, reception, and forwarding with other agencies

- Evaluation of the threat potential of enemy aircraft and missiles, and the selection and assignment of weapons to engage hostile threats

- Engagement control of friendly interceptor aircraft and surface-to-air missiles against enemy threats

- Control of airspace and air traffic within the area of responsibility

- Integration with BACN

Battlefield Air Communications Node: BACN:

The purpose of this system is to extend the radar, data, and radio coverage to remote areas that are inaccessible to ground based systems such as those which are operated and maintained by the 73rd Expeditionary Air Control Squadron. One issue with radios, is that different platforms use different interfaces, and often come into compatibility conflicts. BACN acts as an untethered platform which provides a cross systems interface that allows all weapons systems to communicate. Information that is transferred through a BACN system is then sent and received directly to through the 73rd EACS infrastructure, and is integrated with long-haul communication between Afghanistan and Qatar via satellite. In addition, it offers “knowledge based intelligence” which automatically senses different waveforms characteristics of different senders and receiver, and routes traffic to the appropriate locations. Traditionally, the BACN system was mounted into Bombardier Global Express Aircraft and operated by private contractors from Northrop Grumman (top right/bottom). However, more recently BACN systems are being mounted into EQ-B4 Global Hawk UAVs (top left). While already automated in terms of purpose, this will eliminate the need for pilots and standby operators. Global Hawks are able to fly at higher altitudes able to stay in flight 24/7. Eventually BACN UAVs will be autonomously flown, eliminating the need for operators altogether.

Combined Air and Space Operations Center: CAOC:

The (C)AOC is the senior Tactical Air Control System’s (TACS) agency responsible for the centralized control and decentralized execution of airpower in support of the Joint Force Commander. It acts as the “nerve center” for aerial missions for Operation Enduring Freedom and Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa. It provides real-time air command and control over Afghanistan for thousands of sorties daily. It was linked with Afghanistan in 2009 by the 73rd EACS who built the necessary infrastructure in both Kandahar and Al Udeid Air Base.

Air Support Operations Center

ASOC:

The Air Support Operations Center (ASOC) is an element of the Ground Theater Air Control System (GTACS) which coordinated with the senior Army maneuver unit in theater and is directly subordinate to the Combined Air Operations Center. Organizationally, ASOCs are Air Support Operations Squadrons organized and equipped as an ASOC.

ASOCs are commanded by an Air Force Lieutenant Colonel, it manages allotted air resources and executes missions supporting its aligned Army units. TACPs assigned to an ASOC fill the role of receiving air support requests from forward deployed JTACs. Once an air support request is received, the air support request is either approved or disapproved by the ground commander’s land component chain of command. The following outlines the Air Support Requesting procedures for each decision:

Approved (urgent): Immediate requests to support urgent, troops-in-contact situations may result in strike aircraft being sent by the ASOC to the JTACs location for terminal control of immediate close air support.

Approved (non-urgent): Air support requests submitted after the cut-off time for inclusion on the next Air Tasking Order (ATO), or 24 hour sortie cycle managed by the JFACC, will become scheduled missions on the subsequent ATO.

Disapproved: The disapproved request should be sent back to the requesting unit with reasons for disapproval. It is important to understand that approval and disapproval authority of air support requests is the responsibility of the Army / Land Component being supported.

UAV Sensors:

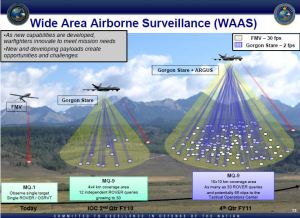

In 2004, the U.S. drone fleet produced 71 hours of video surveillance for analysis. By 2011, that figure was 300,000 hours annually, and today in 2015 it is in the millions. Cameras such as the Gorgon Stare produce so much footage no human could possibly review it all. This has pushed the US military toward programming and using visual intelligence software to review it. Technology exists today with the basic ability to recognize and reason about activity in full motion video. Currently, it is “known” that UAVs can sense movement, heat signatures, gunfire on the ground, and mark it for analysis. The next step is technology like the “Mind’s Eye” (DARPA), which will not only be able to identify and mark potential target, but it will be able to interpret their actions, and alert operators to suspicious activity. The creator once said that targets themselves are the “nouns” on the battlefield, this system seeks to identify the “verbs”. The latest information states that there are currently 48-60 verbs that the system can identify. The following are the tasks this system is programmed to perform.

- Recognition: VI systems will be expected to judge whether one or more verbs is present or absent in a given video

- Description: VI systems will be expected to produce one or more sentences describing a short video suitable for human-machine communication

- Gap-filling: VI systems will be expected to resolve spatiotemporal gaps in video, predict what will happen next, or suggest what might have come before

- Anomaly detection: VI systems will be expected to learn what is normal in longer-duration video, and detect anomalous events.

As a result of the sheer volume of surveillance data currently being processed with sensors such as the Gorgon Stare, it is anticipated that programmes like the Mind’s Eye will be choosing targets for operators themselves. Now I want you to dwell on this thought for a minute…

Back to the Questions:

With everything that I previously mentioned, I want you to ask yourself the same questions I put forth at the beginning of this article.

- Who do you think makes the decisions?

- Commanders?

- Intelligence Officers?

- The TACP/JTAC on the ground?

- The soldier requesting air support?

- The pilot that drops the bombs?

- The team that assembled the bomb and instilled the firing mechanism?

- The network itself?

- All of the above?

- How many people and processes do you think are involved in conducting these strikes?

- Who is ultimately responsible for the end result?

- The soldier who requests the airstrike?

- The commander who provides authorization for the airstrike?

- The pilot who pushed the button that dropped the bombs?

- The intelligence officer that reviewed the footage and marked the targets?

- The people who built and maintained the infrastructure for the network that made any of this even possible?

- Nobody entirely?

- All of the five listed above?

- What is a weapons system?

- Is it the vehicle?

- Is it person commanding the vehicle?

- Is it the person who selects the targets?

- Is the sensors that mark targets?

- Is it the bombs, or is that merely ammunition?

- Is it all of the above and the network itself?

Then I want you to ask yourself a few more questions…

- Who will be responsible for making kill decisions in the future?

- The Secretary of Defense?

- The President?

- Will it be commanders?

- Will it be soldiers on the ground?

- Will it be intelligence officers that review decisions that computer programs have made?

- Or will autonomous weapons system be trusted to the point in which they will be authorized for making the final kill decision?

- Who will feel responsible for fatalities?

- Everyone entirely?

- Everyone somewhat?

- Knowledge of roles, but void of feeling of responsibility?

- Nobody?

- What effect does diffusion of responsibility have on warfare?

- How will network centric warfare, and lethal autonomy affect the future of warfare?

- What affect will this movement have on political decisionmaking?

- How will it affect their decision to use military assets?

- How will the structural use of deadly force be perceived by the public?

- Who will be making the decisions? Private enterprise or Public institutions?

These are just some of the questions that confound me when thinking of what my role actually was in Afghanistan…

Conclusion?

Modern warfare will be described in books as intrastate and asymmetrical, and most assuredly, much will be said about the actual revolutions in the weapons themselves. But what will likely go unnoticed is what the violence actually means to individuals within these modern militaries in relation to the roles they played. Popular culture will continue to focus on the machines of war and less on the networks that structure and support it. The diffusion of responsibility is the nature of modern warfare. This begins with impressionable people who are taught obedience to authority and are provided a legitimizing ideology with social and institutional support. It is further enhanced by linguistic manipulation by the institution to neutralize emotional words, obfuscate processes with acronyms, and rouse feelings that would contribute to desirable outcomes. Furthermore, enlisted servicemen are then taught to respect hierarchies which put command responsibility in the hands of officers. Then the responsibility of the welfare and behavior of the subordinates are put in the hands of the officers. Most of all, the system of punishment for disobedience has evolved from corporal means to administrative means, potentially extending the repercussions over lifetimes, enhanced by social exile. If combined with weapons systems that are coordinated over large distances and require a network of highly specialized operators, sensors, and machine programming just to function properly, then how connected can any “involved” individual be to the use of deadly force on the the ground?

I wrote this paper to hopefully open your eyes to some of the realities of war today. If you hadn’t thought deeply about the things that I mentioned already, then it was the objective of my paper to get you to do so. It has been nearly ten years since I signed the contract binding me to the US military. I was property of the US government until April 18th, 2014. The issues I have discussed affect me greatly. It was my intention to share with you why. It is human curiosity to inquire with those who have participated in war if they have ever killed anybody. If one says no, then the interest often fades. If one says yes, then the inquisitor will often be satisfied with nothing less than a story of horrific conditions, gunfire and explosions. The truth is that many people who said no, may be as equally instrumental in an airstrike as the person that dropped the bomb, we were just too far removed from our actions to feel our part in it. I was a technician, and without what I did, the concept of Network Centric Warfare would still be a concept.

The Ground Theater Air Control System is complicated structure of machines, signals, and humans that span in coverage across the Middle East and Central Asia, but by offering a platform that allows it to operate I would argue that it can and should be considered a weapons system in itself. All parties involved in it are responsible for everything it does. To say otherwise would mean that nobody is responsible, and that the act of killing people in an airstrike is devoid of moral reflection. This is not a world I am willing to live in, and for this reason I refuse to avert my attention from my role in this machine of death and ruined lives. Many would point to the lives this system has saved. Yet I do not view this as any redemption, but rather question the system that made their lives need saving. For every civilian killed, for every man driven to violence as the result of his loved one’s death, for every life it has ruined I understand my place in it. To refuse a system where men and women are diffused of feeling responsibility for the horrors they are complicit with, is to recognize one’s role in this system and to extract oneself from it. The negative emotions which come with it in the beginning overwhelm the senses, fatigue will set in, one will find himself passing through the stages of grief, but in time one begins to understand that guilt has its purpose, through it one becomes more human. From facing it and not suppressing it, we grow as individuals and societies…

The airstrike as I see it, is a metaphor for how our globalized society functions, as we are all facilitators within a great network of injustices around the world. The ethical faults of the United States military are not our own, but they are based on roles we play in social constructs that are sculpted by many processes that reduce our capacities to feel empathy and act accordingly. Similar systems exist all around us and it is our duty to identify them. For this reason, we must all come to terms with who we are in relation to what we do and are complicit with, then sever ourselves from the unseen evils in how we live. Only then can we become more human, and only then can we hope to have a better future than our past.